The Monk, the Wanderer, and Me

Reflections on Caspar David Friedrich’s Paintings (Currently on Exhibition in New York)

I’m heartbroken. Two of my favorite paintings in the world went on display in New York last weekend. I was in the city, but I didn’t know about the exhibition.

Missing the Caspar David Friedrich exhibit that just opened at the Met feels like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity slipped through my fingers.

I was first introduced to Friedrich during my college study abroad program. One of my professors, Gabriel, was an Englishman who had lived in Germany for a decade. He had clearly become obsessed with Friedrich’s paintings, and he passed that obsession on to several of us.

The first of his works I encountered was Winter Landscape in London’s National Gallery. It captivated me. The painting depicts a man who has cast aside his crutches and is praying before a large crucifix. Within the snowy landscape, Friedrich places the cross protruding among three evergreen trees, full of life in the middle of winter. In the background, shrouded in mist, the silhouette of a large gothic church looms ominously.

It's easy to miss the man at first glance as he leans against a boulder. Only when you notice his discarded crutches is your eye drawn through their leading line to him. Has he been miraculously healed, casting down his crutches in celebration and now praying in thanksgiving? Or has he thrown them aside in desperation, pleading with God to heal him? Maybe for the thousandth time? Or has he simply dropped them out of faith, neither desperate nor jubilant, but humbly approaching the Redeemer, trusting in God’s plan for his life?

I naturally saw myself and my experience in chronic pain depicted in the figure of the painting (a common occurrence for me with Friedrich’s work). The ambiguity of the scene mirrors the tension in my own life between resilience and surrender, doubt and faith. Friedrich masterfully captures that tension in many of his paintings.

I grew up surrounded by beautiful art. My mom took us to the Getty Museum in LA and to world-class museums whenever we traveled, sometimes dragging us along to see her favorite paintings. We had a few large prints decorating our house. My favorite was Monet’s Woman with a Parasol. I’ll never forget the thrill of seeing it for the first time in Washington, D.C., in 2013.

My semester abroad built upon the foundation my mom laid. Instead of staying in one place like most study abroad programs, ours spanned 13 countries across Europe and the Holy Land over four months. One of our classes was an art history course, and our classrooms were the great museums of Europe: The Louvre, Rijksmuseum, Musée d’Orsay, Van Gogh Museum, Monet’s Gardens, Kunsthistorisches, Uffizi, Vatican Museums, Galleria Borghese, Gallerie dell’Accademia, and so many others. It was an incredible experience that I underappreciated as a 20-year-old.

The Monk by the Sea

Over the course of that semester, the painting that most dramatically stopped me in my tracks was Friedrich’s The Monk by the Sea in the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin (but currently at the Met in New York. Go see it!). I encountered it almost 14 years ago, but it has haunted me ever since.

The painting is relatively large, and in it, a tiny monk stands on a sliver of land overlooking a churning sea and a massive, ominous sky. The monk is just a few brushstrokes of paint, yet he has captivated my imagination for years. As the sea crashes and the sky threatens, he stands his ground. Is he leaning away in fear or leaning forward in defiance? It’s hard to tell. But his feet are firmly planted.

This is one of the best depictions of prayer I’ve ever encountered in art. The monk perceives the vastness and power of his surroundings. He is minuscule before the endless sky and sea. He is insignificant before the infinite. And yet he remains. He does not run away. By the look of his hand, he is contemplating, beholding the Creator and the raw beauty of creation.

Is it any different for us to stand in the presence of God? We are insignificant before the infinite. We are dwarfed by the vastness and awful beauty of the divine. And yet, in our contemplation, we are drawn into the mystery swirling around us. When we stand on the edge of the open ocean or atop a giant mountain, we become one with creation, encountering and beholding our Creator.

This painting beautifully depicts what I imagine the interior life of a suffering soul looks like. Throughout my 18 years in chronic pain, I have been in the place of this monk by the sea. I have been overwhelmed by the chaos that surrounds me, inside and out. Sometimes, I lean away in fear, and other times, I lean forward out of faith. But no matter what, I hold my ground. Filled with awe and trepidation, I behold my Creator amidst the storm of my life.

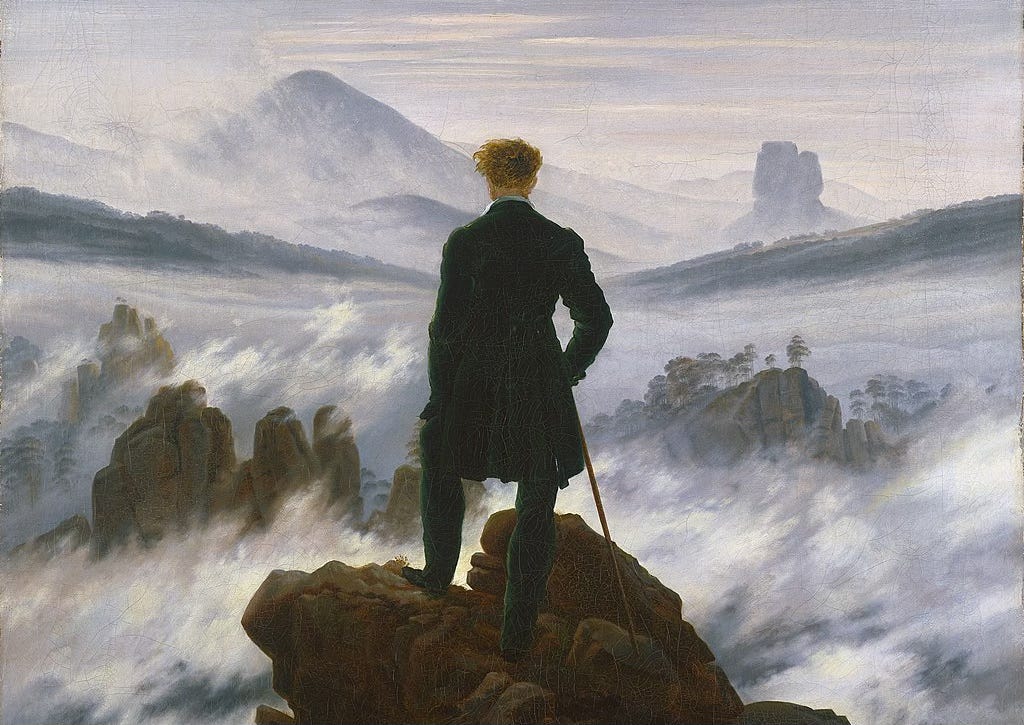

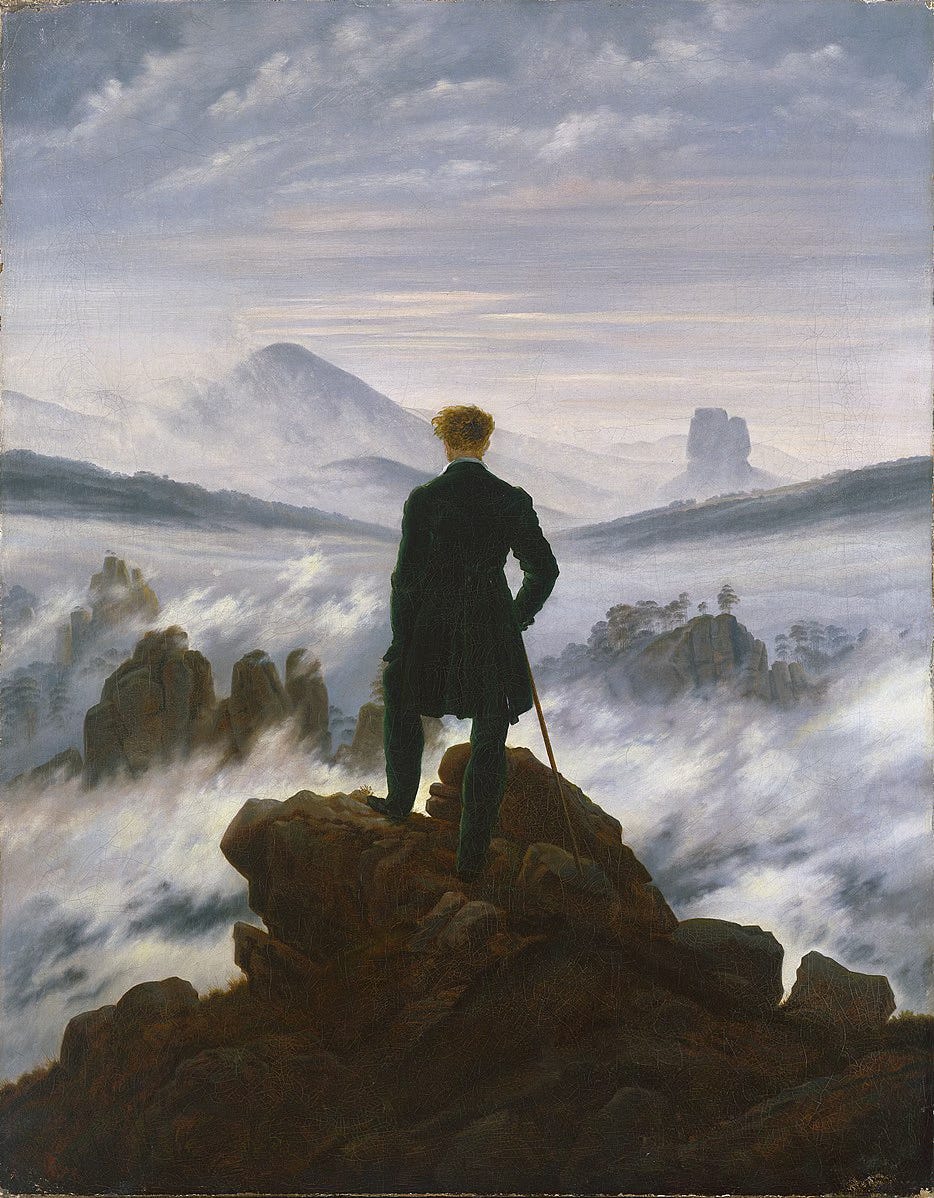

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog

The Monk by the Sea remains my favorite painting I’ve seen in person. However, Friedrich’s most famous work, currently in New York but usually in Hamburg, is my favorite painting overall. I had a large poster of it in my college dorm, and it’s been the background on my phone for years.

The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog is not just Friedrich’s most iconic painting. It is one of the masterpieces of the entire Romantic movement.

At the center stands a well-dressed man, the Wanderer, with his back to the viewer. His posture allows us to project ourselves into his position, and the fact that he’s a redhead makes it even easier for me!

I oscillate between two interpretations of the painting: Is he looking forward or is he looking backward?

Most assume he is looking forward. If so, he sees the path ahead hidden in fog. He can see his presumed destination and a few touchpoints along the way, but the overall journey is obscured. Just like in life, we may know where we want to go and see a few waypoints, but the path itself is hidden. This is the adventure of life. We navigate the unknown, occasionally emerging above the fog to get our bearings before continuing onward. Spiritually, these moments are the “mountaintop experiences” of retreats, pilgrimages, or other encounters with the divine that keep us on course.

But I also love the interpretation that he is looking back, surveying the road he has already traveled. He sees his starting point clearly, but the exact path that brought him to this moment is hidden beneath the fog of experience. The touchpoints he sees are not his next steps but markers of where he has been. They are like the twelve stones Joshua raised on the banks of the Jordan River as memorials of God’s faithfulness. In life, we cannot recall every twist and turn of our journey, but we can place markers to remember the moments that shaped us.

In either interpretation, the Wanderer, like us, does not get to see the whole board. The reality of life remains hidden beneath the fog. We glimpse the beginning and the end, with only a few touchpoints in between. The rest is an adventure on the ground, a daily journey through hills and valleys. Like the Wanderer, we occasionally climb above the fog to catch sight of parts of the trail. We can pause to look back and look forward, but life is not meant to be lived sedentarily on the mountaintop. It is meant to be lived through the journey.

One day, I hope to see this masterpiece in person. I’m genuinely tempted to return to New York before the exhibit closes in May. I would be extremely grateful if anyone could transfer me some airline miles to help with the flight! Realistically, however, I’ll have to go see it in Hamburg another time. Until then, I will continue navigating through the fog, occasionally climbing my own mountaintops, and pressing forward through the adventures of life.